Introduction

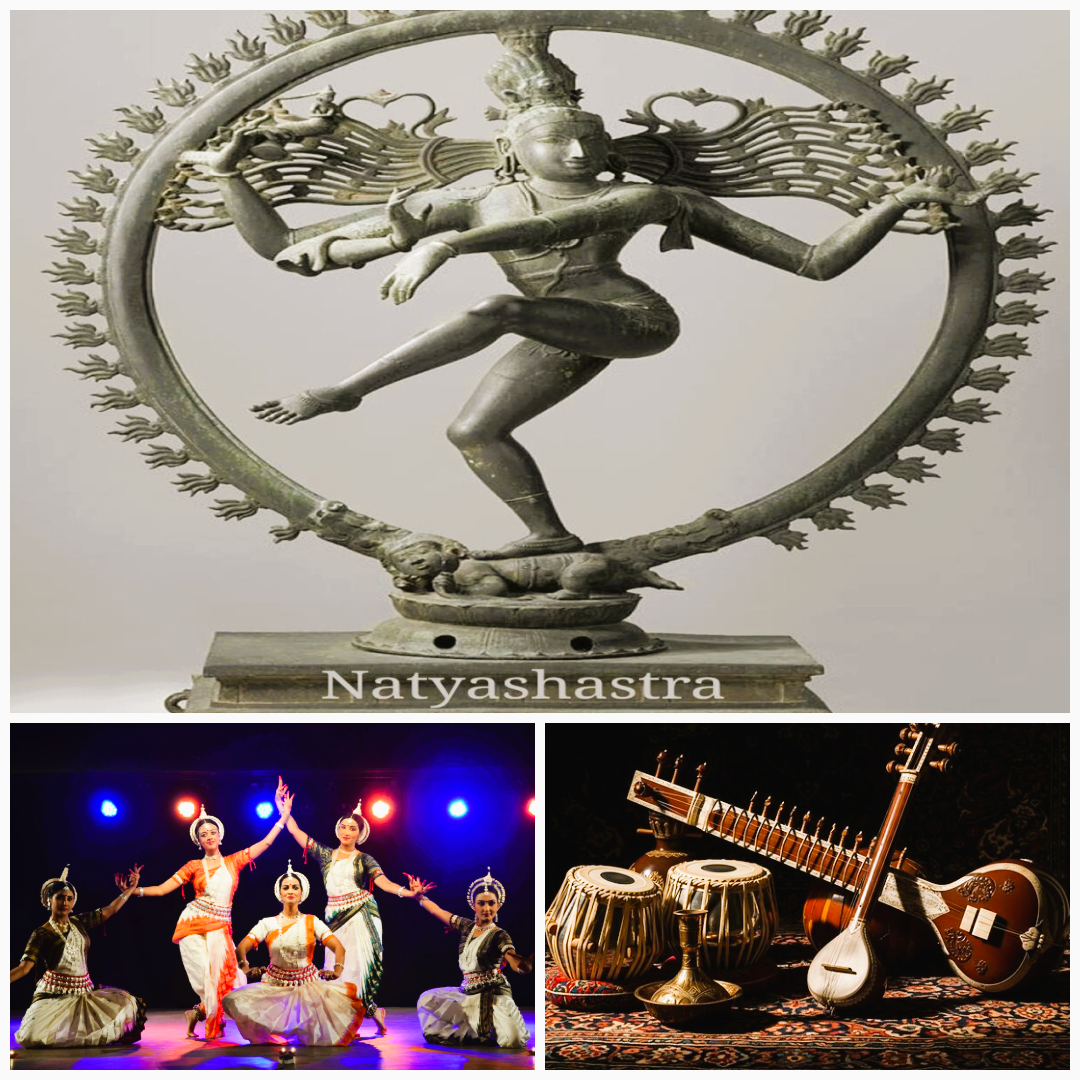

The Natyashastra, composed by Bharata, is one of the most profound treatises on performing arts in India. Among its many contributions, the concept of Karanas stands out as a technical and spiritual foundation of classical dance. The Sanskrit word Karana literally means “doing,” and in the context of the Natyashastra, it refers to coordinated movements that combine posture, hand gestures, and leg actions. Far from being static, Karanas are dynamic units of movement that form the basis of margiperformances those intended to spiritually elevate both performer and spectator.

Karanas in Natyashastra

According to the Natyashastra, mastery of Karanas not only enhances artistic expression but also purifies the performer, freeing them from sins and ensuring divine grace. Each Karana is a composite of three elements:

· Leg movements (charis)

· Hand gestures (hastas)

· Body postures (sthanas)

Together, these create a holistic language of dance that transcends mere entertainment, becoming a spiritual practice. Renowned dancer-scholar Dr. Padma Subramanyam has extensively researched and revived the Karanas, interpreting them as 108 distinct movement phrases involving intricate coordination of hips, arms, and feet, often accompanied by symbolic hasta mudras.

Evolution into Angaharas

Karanas are not isolated; they evolve into larger sequences known as Angaharas.

· Two Karanas form a Matrika.

· Three Karanas create a Kalapaka.

· Four Kalapakas evolve into a Mandaka.

· Five Mandakas form a Sarfighataka.

Some Angaharas consist of six to nine Karanas, creating complex choreographic patterns. This progression illustrates how the grammar of dance builds from simple units into elaborate compositions.

The 108 Karanas

The Natyashastra lists 108 Karanas, each with a unique name and movement style. Examples include Talapuspaputa, Vartita, Apaviddha, Svastikarecita, Bhujanga Trasita, Garudaplutaka, and Gangavatarana. These names often carry symbolic meanings, evoking imagery from nature, mythology, or martial traditions. Interestingly, Karanas were not confined to dance alone. They were employed in martial practices, personal combats, and ritual performances. The footwork aligns with Sthanas (standing positions), while the coordinated gestures embody both aesthetic beauty and functional discipline.

Contemporary Practice

While the Natyashastra prescribes all 108 Karanas, their complete practice has become rare. Some elderly devadasis are known to have preserved the tradition, but in most modern schools of Bharatanatyam and Odissi, only 50–60 Karanas are actively taught. Moreover, the interpretation of the same Karana may vary across different classical styles, reflecting the diversity of Indian dance traditions. Revival efforts by scholars and practitioners highlight the importance of reconnecting with this ancient heritage. By studying and performing Karanas, dancers refine their technique while participating in a timeless spiritual journey envisioned by Bharata.

Historical Context

· The Natyashastra(200 BCE–200 CE) is attributed to Bharata and is considered the foundational text of Indian performing arts.

· Karanas were part of temple rituals, martial training, and storytelling traditions.

· Sculptural depictions of Karanas can be found in temples such as Chidambaram, Thanjavur Brihadeeswara, and Kumbakonam.

Symbolism and Philosophy

· Each Karana embodies cosmic principles, such as Garudaplutaka evoking Garuda or Bhujanga Trasitareflecting a serpent’s trembling.

· They emphasize unity of body, mind, and spirit, aligning dance with yoga and meditation.

· Performing Karanas was believed to be a spiritual offering, transforming the stage into a sacred space.

Technical Aspects

· Karanas belong to margi(spiritual) traditions, distinct from desi (regional) forms.

· They involve precise coordination of Sthanas, Charis, and Hasta Mudras.

· The 108 Karanas are grouped into sequences, enabling complex choreographies.

Influence on Classical Dance

· Bharatanatyam: Many Karanas are embedded, though stylized differently.

· Odissi: Interprets Karanas with fluid transitions.

· Kathakali & Kuchipudi: Use Karanas in martial and dramatic storytelling.

· Regional variations mean the same Karana may look distinct across traditions.

Modern Revival

· Dr. Padma Subramanyam reconstructed Karanas from texts and temple sculptures.

· Contemporary dancers aim to reintegrate all 108, though most schools teach 50–60.

· Workshops and research projects continue to preserve this heritage.

Cultural Significance

· Karanas are cultural markers linking performance, spirituality, and social life.

· They blur boundaries between aesthetic beauty and religious devotion.

· Their endurance across centuries shows adaptability and timeless relevance.

Conclusion

Karanas in the Natyashastra represent more than physical movements; they are the sacred grammar of Indian Classical Dance. Rooted in philosophy, ritual, and aesthetics, they embody the union of body, mind, and spirit. Whether performed in temples, theatres, or modern stages, Karanas continue to bridge the ancient with the contemporary, reminding us that dance is not just art—it is a path to transcendence.