Stretching like a glimmering ribbon through the heart of Kerala, Vembanad Lake is not only the longest lake in India but also the country's largest wetland ecosystem. Known for its extraordinary hydrographic characteristics, The Lake represents an interplay of freshwater and saline environments, forming dynamic aquatic landscape rich in biodiversity and cultural significance.

Geographical Spread and Hydrological Features

Vembanad Lake sprawls across multiple districts Alappuzha, Kottayam, and Ernakulum covering an estimated surface area of 200 square kilometers. The lake is a part of the extensive Vembanad-Kol wetland system, which, at over 96.5 kilometers in length, is the longest of its kind in India. The hydrography of Vembanad reflects a unique estuarine ecosystem where freshwater from ten rivers, including major ones like Periyar, Pamba, Meenachil, Manimala, and Achenkovil, converges with saline waters from the Arabian Sea.

The lake sits at sea level, separated from the Arabian Sea by a narrow barrier island. It surrounds several small islands such as Pathiramanal, Perumbalam, and Pallippuram, further enhancing its hydro-ecological complexity.

An area of 398.12 square kilometers lies below mean sea level (MSL), and over 763 square kilometers lies below 1 meter MSL, making this low-lying basin prone to tidal fluctuations, seasonal flooding, and diverse aquatic processes. This fragile interplay between water levels, salinity gradients, and sediment movement shapes the ecological functions of the lake.

Hydrography and Ecological Balance

The hydrography of Vembanad embodies the intricate relationship between water and life. Fed by a substantial portion of Kerala’s river systems, the lake is central to water transport, irrigation, fisheries, and traditional livelihoods. The brackish nature of its water allows for a broad range of aquatic organisms, including freshwater species in the upper stretches and marine life in the lower saline regions.

However, the equilibrium is not solely natural — human interventions play a decisive role. The most prominent example is the Thanneermukkom Saltwater Barrier, a 1,252-meter-long mud regulator, built under the Kuttanad Development Scheme. This unique structure divides the lake into two distinct hydrological zones:

Freshwater Region: On the eastern side, fed by river inflows, useful for irrigation and agriculture.

Brackish Water Region: On the western side, influenced by tidal action, beneficial for backwater tourism and fishing.

This man-made intervention supports double-cropping in Kuttanad by controlling salinity but also alters fish migration and affects sediment transport, demonstrating how closely water management and ecology are intertwined.

Biodiversity and Wetland Importance

Vembanad Lake is a designated Ramsar site, highlighting its global ecological importance. It’s wetland habitat supports an astonishing array of flora and fauna. Thousands of migratory birds’ nest in its marshes, particularly in the Kumarakom Bird Sanctuary, located on the northern edge of the lake. The region harbors species like darters, egrets, herons, and terns, making it a haven for ornithologists and eco-tourists alike.

The aquatic vegetation — including water hyacinths, lotus, and reeds — forms the backbone of the lake’s ecological productivity, enabling fish breeding and maintaining water quality. The health of this wetland ecosystem is vital not just for biodiversity but also for the livelihoods of local communities who rely on fishing, coir processing, and rice cultivation.

Tourism and Cultural Significance

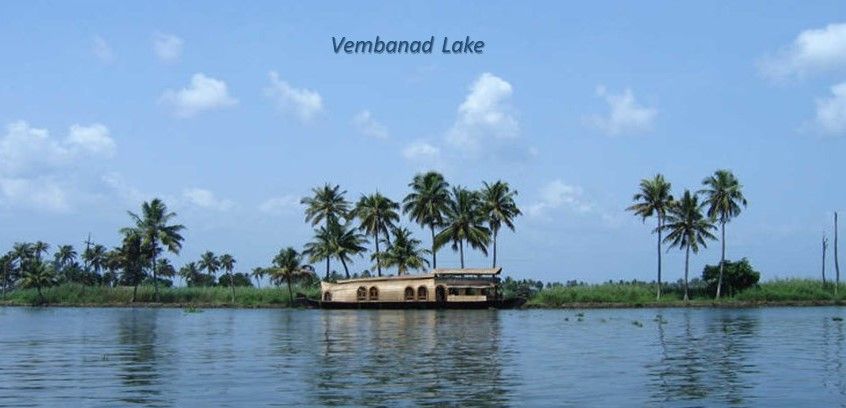

As Kerala’s tourism crown jewel, Vembanad offers more than just scenic beauty — it delivers a cultural experience deeply tied to water. The lake plays host to vibrant events like the Nehru Trophy Boat Race, which draws spectators from around the globe. Traditional snake boats (chundan vallams) slicing through the mirrored waters present a thrilling visual of communal celebration and athleticism.

The Kumarakom Tourist Village, perched on the lake’s east bank, is a hotspot for backwater cruises, Ayurvedic retreats, and eco-tourism. Houseboat journeys across the lake are popular for their tranquil charm and immersive view of Kerala’s rural life. These experiences blend natural splendour with cultural richness, attracting travelers seeking rejuvenation and connection with nature.

Hydrological Challenges and Conservation Needs

Despite its grandeur, Vembanad faces a number of environmental pressures. Unregulated urbanization, agricultural runoff, invasive species, and effluent discharges have led to reduced water quality, sedimentation, and shrinking wetland area.

Hydrologically, these issues affect the flushing capacity of the lake, altering salinity regimes and threatening aquatic life. The obstruction of tidal movements by the saltwater barrier has also led to water stagnation in some areas, triggering eutrophication and algal blooms.

To safeguard the lake’s hydrography and ecological value, integrated measures such as sustainable tourism, participatory wetland governance, and pollution control are essential. Community awareness, policy support, and scientific monitoring can ensure Vembanad retains its lifeline status in Kerala’s socio-ecological fabric.

Conclusion

The hydrography of Vembanad Lake is more than a study in water geography — it is a living portrait of Kerala’s relationship with nature. A cradle of biodiversity, a beacon of backwater Tourism, and a reservoir of cultural pride, the lake encapsulates the soul of the region. Its unique blend of freshwater and brackish systems, shaped by both natural and engineered influences, illustrates the complexities of managing delicate ecosystems in the face of modern pressures.

As Kerala continues to stride forward, Vembanad Lake must remain a priority for conservation, education, and celebration — a shimmering reminder that water, in all its movements, is life in motion.