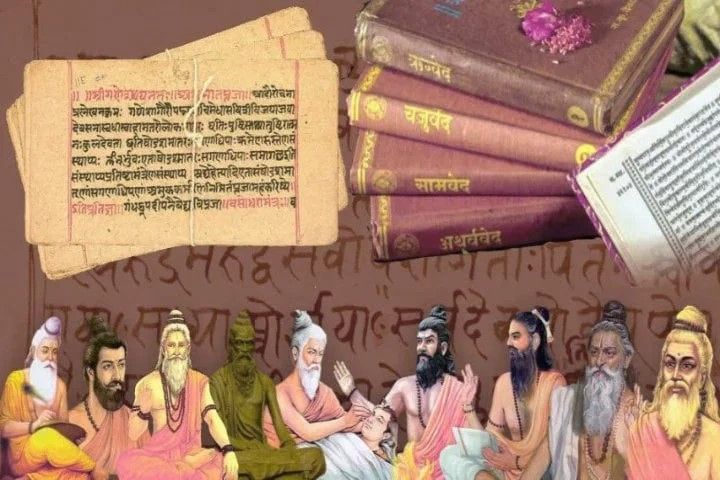

Ancient India, a land of profound philosophical thought and rich cultural diversity, boasts a history stretching back millennia. Examining Ancient Indian Customs offers a unique window into the societal structures, beliefs, and daily lives of the people who shaped this civilization. Fortunately, a wealth of information on these customs survives within the vast corpus of Sanskrit and Indo-Aryan Literature, revealing fascinating details about everything from marriage rituals and familial relationships to religious practices and societal values.

The Vedic Age: Foundations of Tradition

The Vedic period, the earliest phase of Indo-Aryan civilization (circa 1500-500 BCE), is primarily known through the Vedas, a collection of hymns, prayers, and philosophical treatises. These texts offer a glimpse into the aspirations and customs of the early Aryans. The Rig Veda, in particular, reveals a desire for worldly prosperity, including long life, abundant livestock, brave sons, and victory over enemies. Beautiful women were held in high regard, reflecting a patriarchal society.

Marriage ceremonies were significant events, marked by the giving of gifts by the bride's father. Both the bride and groom were adorned with finery. While specific age restrictions for girls weren't explicitly defined, a long and prosperous married life was considered paramount. The wife's place within her husband's home was seen as honorable. The Rig Veda also highlights the concept of familial support, with customs like maintaining a son-in-law or brother-in-law who was unable to provide for himself.

While the Vedic texts acknowledge the existence of "sinful deeds," they don't elaborate on specific acts. Instead, they suggest that the effects of sin could be mitigated through prayers and rituals. Curses were a common societal feature, and the Rig Veda mentions various crude forms of punishment.

Interestingly, the birth of a son was celebrated, while the birth of a daughter was often met with less enthusiasm. A girl without brothers was considered less desirable for marriage, and certain physical traits like blemishes on the forehead or "fierceness of looks" were considered unfavorable.

The Age of Brahmanas: Elaborating on Rituals and Social Norms

The Brahmana texts, commentaries on the Vedas, shed light on more detailed rituals and social structures. They reveal curious customs surrounding the disposal of the deceased. If a householder who maintained the sacred Garhapatya fire died and their body couldn't be found, an effigy was created and cremated in its place.

Marriage practices evolved during this period. While other forms of marriage existed, the Swayamvara, where a bride chose her husband from a gathering of suitors, was in vogue. Polygamy seems to have been relatively common, while polyandry (a woman having multiple husbands) was generally prohibited. Inter-caste marriage was practiced, though marriage within the same caste was considered ideal. In cases of inter-caste marriage, the husband typically belonged to a higher caste than the wife.

Family life was governed by specific customs. A wife was expected to wait for her husband to eat before partaking in her own meals. The husband was to sleep on the right side of his wife. The daughter-in-law was expected to show utmost respect to her father-in-law and remain out of his direct sight. Furthermore, there was a prevalent belief that women were fickle-minded and that true friendship with them was impossible.

Kalpasutras: Formalizing Marriage and Family Life

The Kalpasutras, manuals of ritualistic practices, offer further insight into marriage customs and societal expectations. They reiterate the preference for intra-caste marriage while allowing inter-caste marriage provided the husband was of a higher caste. The Brahmana texts emphasized that the form of marriage directly influenced the quality of the progeny. The Gandharva form, based on mutual love, was sometimes condemned for Brahmanas.

The sutras mention the eight traditional forms of marriage but strongly condemn the Rakshasa and Pisaca forms, where the bride is either captured by force or seduced. Apastamba emphasizes that marriage is a sacred union established through dharma, implying that force could not create a legitimate marital relationship. This suggests that even if a forced marriage occurred, societal norms might have recognized it under the principle of Factum Valet(a deed valid in itself) to protect the social standing of the woman.

The Kalpasutras also delve into the ideal age for marriage, emphasizing that the bride should be younger than the groom. However, the specific age remained a point of contention. Qualities like excessive sleep, fondness for games, or having a beautiful younger sister were considered undesirable in a bride.

The auspicious time for marriage was also debated, but the custom of showing the sun to the bride suggests that marriages were often celebrated during the daytime. After arriving at the husband's home, the wife was expected to spend her first night at the house of an elderly Brahamana woman with a living husband and children. The practice of placing a boy on the bride's lap was also common, often the son of a woman with only sons, all still living, to ensure the birth of a male child. This practice reinforces the patriarchal preference for sons over daughters.

Later Developments: Panini, Patanjali, and the Epics

The writings of Panini and Patanjali provide further glimpses into ancient Indian society. Panini distinguished between two modes of invitation for feasts: nimantrana and amantrana. Patanjali's Mahabhasya suggests that polygamy was prevalent in society. Similar to earlier periods, the birth of a son was celebrated, while the birth of a daughter was not always hailed.

The great epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, offer valuable insights into the culture of ancient India. The Ramayana mentions ceremonies celebrating the harvest season, where people gathered to partake in the first grains after offering them to the gods and ancestors. The veneration of cows was a significant feature of society, with the killing of a cow considered a grave sin.

The Mahabharata provides evidence of polyandry, as seen in Draupadi's marriage to five brothers. The Gandharva form of marriage was also common. The epic reflects a more warlike society than the Ramayana. While the importance of sons remained, women were generally highly honored. Husbands were advised to treat their wives with respect and kindness, recognizing them as embodiments of the goddess Lakshmi. Wives, in turn, were expected to prioritize their husband's comfort and adhere to his wishes.

Conclusion:

Through these literary works, a rich tapestry of ancient Indian customs unfolds. From the Vedic period to the age of the epics, these customs provide a glimpse into the values, beliefs, and social structures of Ancient Indian Society. While patriarchal tendencies and preferences for sons are evident, the texts also reveal instances of women being honored and respected. Studying these ancient customs offers invaluable insights into the complex and fascinating history and Culture of India. These ancient traditions, even as they evolved and transformed over time, laid the foundations for many of the cultural practices and societal norms that continue to resonate in India today.